Sentence Analysis of Something Wicked This Way Comes by Ray Bradbury

Deliberate Practice: Something Wicked This Way Comes

Today, I will do some sentence analysis of Something Wicked This Way Comes. . What is it about his sentences that makes his prose here so appealing.

The seller of lightning rods arrived just ahead of the storm. He came along the street of Green Town, Illinois, in the late cloudy October day, sneaking glances over his shoulder. Somewhere not so far back, vast lightnings stomped the earth. Somewhere, a storm like a great beast with terrible teeth could not be denied.

So the salesman jangled and clanged his huge leather kit in which oversized puzzles of ironmongery lay unseen but which his tongue conjured from door to door until he came at last to a lawn which was cut all wrong.

Ray Bradbury, Something Wicked This Way Comes

Diagramming Sentences

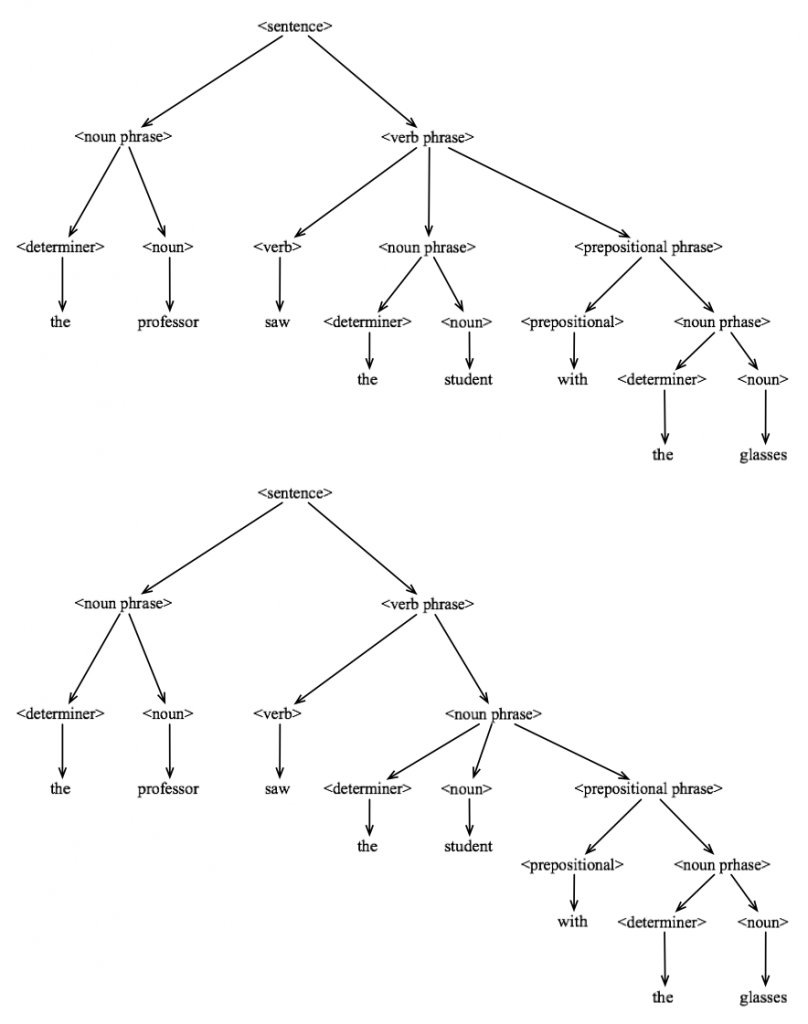

Sentence Analysis can be complex. One method of breaking down a sentence is to use a sentence diagram.

You will know that I am fairly convinced that what makes us think a sentence is good arises from the sound and rhythm and only marginally from the sense of the words.

Despite that, I considered whether it would be worth attempting to diagram the sentences.

You remember that a formal sentence analysis diagram shows a sentence by its grammatical components. So:

However, I’m not sure that this kind of sentence analysis adds anything to understand the prosody: how the prose flows and sounds nice.

It may have some use in understanding how the author puts together the sentences, in fact, it probably does. However, the technical look of the diagram may actually be a barrier to understanding to those who are not familiar with sentence diagramming already.

In the same way, there may be a wonderful analysis of a piece of writing written in Arabic, but if you don’t read Arabic, it’s not much use to you.

I think I will give up sentence diagramming for now.

Sentence Analysis: Length

[***********.]

[********,*,******,*****.]

[*****,*****.]

[**************.]

[****************************************.]

Sentence Analysis: Structure

Refer to the Anotation Scheme

[___( )]

[___ ( ) ( ) ( )]

[( )( ) ___]

[( )___( )___]

[___ ( ) = > ( ) ( ) ^ ( ) > ( )]

Here we see a baby cumulative sentence with one clause after the main clause ___ ( ) and then we see a nice cumulative sentence __ ( ) ( ) ( ) which has a lovely rhythm. The next two sentences are front-loaded with dependent clauses.

The final sentence is another cumulative sentence ending in a trail of dependent clauses strung together with coordinating and subordinating conjunctions and relative pronouns.

A good cumulative sentence lets the rhythm settle like an echo fading away.

Sentence Analysis: Grammar

See here

- Noun Group (subject) + Verb + Adverbial of Time

- Pronoun (subject) + Verb + Adverbial of Place + Adverbial of Time + Adverbial Participial Clause

- Adverbial of Place + Adverbial of Place + Noun Group (subject) + Verb + Object

- Adverbial of Place + Subject + Simile Noun Group (re-stating the subject) + Verb (passive)

- Conjunction + Subject + Verb + Verb + Object + Relative Pronoun + Conjunction + Relative Pronoun + Verb + Adverb + Conjunction + Relative Pronoun + Relative Clause + Adverbial Clause + Subordinating Conjunction + Subordinate Clause + Preposition + Object + Adjectival Clause

I’m not sure what that tells us.

Sentence Analysis: Rhetorical Devices

See here

Anaphora: “Somewhere not so far back,…” repeated “Somewhere, a storm…”

Alliteration: Lots of l and s. Does that sound like a storm?

“…seller…lightning…along…glances…lightnings…like…leather…lay…last…lawn”

“terrible teeth”

“Somewhere not so far back…stomped. Somewhere a storm…salesman”

Assonance/Rhyme: “jangled and clanged” “street … Green”

Use of Doubles, Triples: Very often a writer will use two adjectives or two nouns or two verbs coupled with an “and”. These doubles are not essential to the sense of the writing, and are used to either add detail, or most often improve the sound.

So: “jangled and clanged” say more or less the same thing. They are included for the sound not the meaning.

Of course sometimes doubles and troubles add both sound and meaning to a piece of writing.

Metre

Again, this is to my ear, reading aloud.

- u Su u Su S uSu u uS u u S.

- u S uS u S u S S, SuS, u u S Su uSu S, Su Su Su u Su.

- Su S u S S, S Su Su u S.

- Su, u S u u S S u Suu S S S u Su.

- S, u Su Su u S u S Su S u S SuSu Su u SuSuu S uS u u u S Suu u S u S uS u S u S u u S u u S S S.

Unless it is my ear, there are no remarkable patterns here. Some iambs.

Conclusion

The main clause tells us the bones of what is going on.

“The seller…arrived…”

The subordinate clauses add description. Technically >of lightning rods< is not a clause or even a fragment, but it adds description to the “seller”, so I’ll use one word for the bits that add detail.

Ultimately I wonder whether nounds, adjectives, adverbs and prepositions are really distinct things in our mind. All we see is a process wherein the subject, object and verb (not to mention the indirect object) are indissoluble. When I touch a glass vase, I only have one experience and the division into what part of that sensation is glass and what part of that sensation is me is very post hoc. There is no division in experience, only in processing and naming. Same with verbs, subjects and objects.

“The seller (of lightning rods) arrived (just ahead of the storm).

All the clauses add a bit more detail to the picture. The author can choose where to put the clauses, more or less, and it is this choice that affects the rhythm of the prose and sets up patterns of metre or alliteration or any other rhetorical device.

“He came along the street (of Green Town(, (Illinois), (in the (late) (cloudy) (October) day), (sneaking glances over his shoulder).”

All the words in parentheses are not strictly necessary. However, they make the picture of the event clearer in our mind.

We may say that the white in a Monet painting is not strictly necessary, or the salt in some soup, or that quaver in a Mozart piece.

They’re not necessary, but without them the picture is impoverished.

But we could re-arrange the clauses for rhythm and other effects.

(Sneaking glances over his shoulder), (in the late October day), (along the street of Green Town, Illinois), the seller of lightning rods came.

Or …came the seller of lightning rods.

That inversion of verb is just what they do in German and Dutch most of the time so it’s a relic of English’s West Germanic roots.

And putting the main clause at the end would make it a periodic sentence.

A cumulative sentence tells you what it’s about straight away, and thus no Zygarnik tension, no unclosed loop. We expect information and until the bare bones sense of the sentence is transmitted we remain slightly anxious.

The cumulative sentence relieves the anxiety straight away, and then adds detail to our delight in a sort of cannon shot that echoes pleasingly in th valley.

The periodic sentence witholds the key information until the very end, maintaining our tension, so even though we get the additional information we rush by it, wanting to know what this is additional to.

The the cumulative sentence is like a cannon shot that echoes away to nothing, the periodic sentence is like waiting for the firing squad.

So it seems it may not just be about sound and rhythm as I have put forward elsewhere.

This is an affiliate link, so if you buy this, it helps me.

Here‘s a review of Something Wicked this Way Comes from The Guardian